5 Books to Read for Disability Pride Month

By Amy Denton-Luke

July is Disability Pride Month, a time to celebrate the disabled community and our resilience in the face of ableism and adversity, as well as a time to raise awareness for the inequalities and injustices that disabled people continue to face today. In honor of this month, here are a few book recommendations for both disabled and non-disabled folks to learn about the history, the movements, and the lived experiences of disabled people.

#1: Demystifying Disability: What to Know, What to Say, and How to be an Ally

by Emily Ladau

“There’s a philosophy I’ve come to embrace that informs everything I do: If the disability community wants a world that’s accessible to us, then we must make ideas and experiences of disability accessible to the world." -Emily Ladau (Pg 2)

Summary: Demystifying Disability is a great “Introduction to Disability 101” book for both disabled and non-disabled folks alike, covering important basics and a wide variety of topics.

Topics discussed: Definitions of disability and other terminology, types of disabilities, models of disability (i.e. social, medical), a brief overview of disability history in the US (eugenics, forced sterilization, Americans with Disabilities Act), movements (e.g. disability justice), ableism and accessibility, disability etiquette do's and don't’s, disability representation in media (inspiration porn, pity/tragedy tropes), and tips for how to be an ally.

My main takeaway: Every person has more to learn and unlearn about disability, whether we are disabled or non-disabled.

Discussion: Demystifying Disability is a great casual read that offers an introduction into many different aspects of disability. I related to a lot of the sections and had a few laughs, like the author’s critique of the cringeworthy, ableist movie Me Before You. I also had a few moments of, "Ugh, yes, thank you,” like the discussion on how patronizing it is when able-bodied folks try to act like they understand what you're going through by comparing it to their own (very minor) illness or injury experience. I've had people do this with colds and sprained ankles and, while I can appreciate that people are trying to relate and connect, it's actually quite insulting.

Non-disabled people will benefit from the practical, everyday knowledge that is shared in this book. For example, the section on language tells readers to use the word "disabled" and avoid euphemisms like “special needs”, “differently abled”, or “handi-capable”. The discussion on inspiration porn explains why it's not inspiring to share news stories about a disabled teen getting asked to prom, or memes with the quote, "The only disability in life is a bad attitude". The etiquette section teaches readers not to touch anyone's mobility aids without permission, because unfortunately there are people out there who will actually push wheelchair users out of their way. This chapter also cautions readers against making rude and unnecessary comments (for example, saying to a wheelchair user, "You got a license for that thing?"), asking nosy and inappropriate questions (such as, "Can you have sex?”), and offering unsolicited advice (like the all-time favorite classic, "Have you tried yoga?").

Demystifying Disability is a wonderful book for non-disabled folks to be introduced to disability, but also for disabled people to deepen our understanding of disability, too. It’s important to remember that we have all been raised and conditioned in an ableist society, so we all have learning and unlearning to do when it comes to how we perceive and think about disability, even if we are ourselves disabled. As Ladau notes, “There’s no magical force field preventing disabled people from being ableist” (Pg 75).

Disabled people will benefit from reading the sections on disability models, movements, and history, as well as the discussion on privilege and intersectionality. Ladau explains, "The other identities that people have in addition to disability can impact both how they experience disability and how people perceive and treat them" (Pg 31). She offers a powerful example by doctoral student D'Arcee Neal: “People need to recognize that being Black means you’re perceived as being criminal, whether you have a disability or not,” he says. “When I tell people I have cerebral palsy, they’re surprised because that’s not the first association they made with why I’m a wheelchair user. When I was younger, the very first question most white people would ask upon meeting me was ‘When were you shot?’" (Pg 33). Acknowledging intersectionality, privilege, and the ways in which oppressive systems are intertwined is essential for unlearning and dismantling ableism, which will be discussed later in this blog post.

Ableism is so ingrained into our society that we don’t always notice it, and the book’s chapter on ableism and inaccessibility will bring some examples to light. More people should be aware that it is still legal to pay disabled people subminimum wage, or that only 25% of New York subway stations have elevators. Ladau explains that "many people operate on the assumption that disabled people don’t have full lives that might require public transportation" (Pg 71). Indeed, this is a common issue: non-disabled people don’t consider that disabled people are just regular people who may want or need to visit all of the same places that non-disabled people visit. Inaccessibility is also common, and the excuse people frequently give for why they do not make a space accessible is that “disabled people don’t come here, so what’s the point of making it accessible?” Ladau points out that this is not only inaccurate, because nonapparent disabilities exist, but it's also likely that the lack of accessibility is the reason that disabled people are not visiting these spaces in the first place (Pg 79-80).

I really appreciated Ladau’s insights and learned quite a bit myself. For example, the issue with using phrases like "high functioning" and "low functioning", or that there are various definitions of disability by people with disabilities. How disabled people define and describe themselves is deeply personal, and we each have our own preference (Pg 10). Also, while no group is a monolith, this is especially true for disabled people. There is no singular disability experience and Ladau really put this into perspective for me. How someone with a mobility disability experiences and perceives disability is different from a person with a chronic illness or cognitive disability, or how a blind person, Deaf person, or autistic person identifies with disability. Furthermore, even people within the same diagnosis or type of disability will have a unique experience and perception of disability. It depends on so many factors, including if they were born with a disability or acquired it later in life, whether their disability is visible or not visible, how their culture views disability, how their other identities intersect with disability, and even the person themselves (Pg 31).

Because each disability experience is unique, if you know a disabled person, then you know just one disability experience, or if you yourself are disabled, then the only disability experience you are an expert on is your own (Pg 4). So there is always more to learn about disability, whether we are disabled or non-disabled, and Demystifying Disability is a wonderful place to start.

#2: Disability Visibility: First Person Stories from the Twenty-First Century

Edited by Alice Wong

“For those of us with congenital conditions, disability shapes all we are. Those disabled later in life adapt. We take constraints that no one would choose and build rich and satisfying lives within them. We enjoy pleasures other people enjoy and pleasures peculiarly our own. We have something the world needs." -Harriet McBryde Johnson (Pg 10)

Summary: Disability Visibility is a collection of essays by authors with a wide range of backgrounds and disabilities discussing a variety of disability-related topics.

Essay themes include: Crip culture (crip time, the beauty of spaces created by and for disabled people), daily life (assistive technologies, parenting with a disability), careers (making innovative contributions to the field as a blind astronomer, dancing in a wheelchair), inaccessibility (being Deaf in prison, New York City’s paratransit system), ableism (eugenics, being autistic and told you're a lost cause), and a variety of disabilities (being tired of chasing a cure for chronic illness, institutionalization for people with intellectual disabilities, guide dogs and Blind people wandering as one, stigma and shame around incontinence), plus intersections of religion (fasting for Ramadan when you have cerebral palsy, the pressure to be healed from an eye condition in church), race (how Black disabled people are impacted by state violence, Black disabled joy), ethnicity (the erasure of Indigenous people in chronic illness and discrimination in healthcare settings, being an immigrant and coping with both East Asian and US perceptions and attitudes toward disability), and gender/sex/sexuality (a eulogy for a proud Black disabled trans man, asexuality and disability), and more!

My main takeaway: The disability experience varies tremendously, and our greatest challenges often don't come from disability itself.

Discussion: Disability Visibility is a profound and important collection of essays that reveal myriad aspects of life for disabled people, offering the reader brief yet deeply personal glimpses into the lives of disabled people who come from a wide range of perspectives. I learned a lot from reading the thoughts and experiences of people who have different disabilities and identities than me, and it gave me a deeper sense of community and belonging.

"The Beauty of Spaces Created by and for Disabled People," by s.e. smith describes an experience attending a dance performance in which both the dancers and the audience members were disabled. smith recalls the canes dangling from seat backs, the ASL interpreter next to the stage, and the wheelchair and scooter users out in front. They then describe the giddy feeling and “vivid belonging” that one feels the first time you’re in a social setting inhabited entirely by disabled people: "It is very rare, as a disabled person, that I have an intense sense of belonging, of being not just tolerated or included in a space but actively owning it; ‘This space,’ I whisper to myself, ‘is for me’” (Pg 271-272). smith goes on to say that being in a space where disability is celebrated and embraced is "energizing and exhilarating". I look forward to getting this experience myself someday, as I have only ever been in crip spaces online and I imagine the feeling of belonging is even more intense in person. In a week, I'll be going to a comedy show called the "Comedians with Disabilities Act" and I'm not only excited to see disabled comedians talking about disabled things, I'm excited to sit in an audience full of disabled people. To be in a crip space talking about crip things with other crips will be an exhilarating experience indeed.

Of all the essays, I related the most to "I'm Tired of Chasing a Cure" by Liz Moore, because of their descriptions of various chronic illness things that many chronically ill people know all too well: the therapists who claim they have experience with chronically ill patients, but clearly demonstrate they don't understand what it's like to have such limited energy and how it affects daily life; the internalized ableism early in illness and the endless attempts at "cures" that don't exist, like losing weight, avoiding gluten, and the absurd, "if only I don't say I have fibromyalgia, perhaps I won't have it" (Pg 76); the medications, the physical therapy, the doctors who don't take insurance; at times getting sicker in the quest for cure; the difficulty in accepting that these agonizing symptoms are just your normal now; the myth that "if I only tried hard enough, disability would not be a problem" (Pg 77). And in all that time searching and suffering, to have only accomplished survival; that if we spend all of our time searching for cures, we will never have a life at all.

I also really appreciated Moore’s discussion on the idea of "cure" in disability communities, which is a much more complex and nuanced topic than many people realize. It may be surprising to some to learn that not every disabled person wants a cure; that not everyone considers themselves "broken" and in need of fixing. For many people in the autistic and Deaf communities, as well as many folks who were born with disabilities, erasing disability is akin to erasing Self; it is so closely intertwined with who they are, that it is not possible to separate the two. On the other hand, for people with chronic pain or chronic illness, the idea of cure from pain or fatigue and other symptoms would come as a welcome relief. It truly depends on the disabled person and their disability, and I think it's important to understand this multitude of perspectives and not make assumptions that everyone wants a cure or that nobody wants a cure.

“Six Ways of Looking at Crip Time” by Ellen Samuels was one of my favorite essays. "Crip time" can be an endearing term used by the disabled community to describe the experience of doing things according to our body's needs, working around the requirements and timeframes of our illness and disabilities rather than clocks. However, Samuels points out a few other ways of looking at crip time— the more difficult-to-swallow aspects of crip time that I think many disabled people will recognize. "Crip time is time travel", Samuels says. We fast forward to old age without being awarded the opportunity to once be young and healthy and free. "Crip time is grief time", the crushing losses that we endure. "Crip time is broken time", forcing us to find new patterns and rhythms, to take breaks even when we don't want to. Crip time "insists that we listen to our bodyminds so closely, so attentively, in a culture that tells us to divide the two and push the body away from us while also pushing it beyond its limits" (Pg 192). "Crip time is sick time"; being too sick to work and too sick to go to school. "Crip time is writing time" and taking forever to finish projects— one that I know all too well. "Crip time is vampire time", of "late nights and unconscious days", and how "the body confines us like a coffin, the boundary between life and death blurred with no end in sight” (Pg 195).

While some essays were relatable, others helped me to learn from the experiences of people who have different disabilities than I do. For example, in "On NYC’s Paratransit, Fighting for Safety, Respect, and Human Dignity," Britney Wilson shares her experiences attempting to navigate poorly funded and poorly run accessible transportation, which she has no choice but to use because, as mentioned earlier, only 25% of NYC’s subway stations are accessible. Wilson describes enduring the hours-long roundabout excursions to your not-far-away destination, sometimes driving past your destination to drop off other passengers just to come back to it when it's your turn on the schedule, as well as dealing with the sometimes rude, unsafe, and inappropriate behavior by drivers along the way. I also learned from the experiences of disabled people who have different identities than me and the challenges they face that I have had the privilege not to. In "The Erasure of Indigenous People in Chronic Illness," Jen Deerinwater shares her experiences in healthcare settings as a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, including being asked degrading questions, treated like a museum relic, harassed about her ethnicity, and called a slur by hospital employees.

Jen Deerinwater’s essay was an important voice to include in this book, because it is one that is typically ignored and excluded in discussions about disability (and everywhere else, really). As a result, we don’t hear about issues that affect Indigenous peoples, like the fact that Indigenous people die at significantly younger ages than all other ethnic groups, due in part to the poor healthcare they receive. Deerinwater explains, “The only healthcare available to Native people living on reservations is provided by the Indian Health Service”, which is consistently rated as the worst healthcare provider in America (Pg 48). Additionally, the IHS receives significantly less funding than the federal prison system, there aren’t enough healthcare clinics or hospitals to serve reservations and tribal villages, and reproductive healthcare is virtually unavailable (Pg 49). This is why it is so important to include multiply marginalized people in conversations on disability. When awareness around disability rights focuses entirely on white experiences, it erases the important voices and perspectives of people who also deserve to be heard and have their concerns addressed.

There are some essays in this book that are tough to read due to the heavy subject matter, and any potentially triggering topics are clearly marked at the beginning of each essay with “content notes” above the title, so that you may choose which essays to read and which ones you might want to skip. Some essays are just a few pages while others are longer, and there's a good variety of topics and moods, which makes it easy to read in smaller chunks. I liked that I could read one or two stories then take a break, instead of committing to long 20 page chapters, which made this book more accessible for me and my brain fog.

Finally, I would like to point out that while some of these essays describe the challenges of the author’s illness, disability, or bodymind directly, many of the essays are more about the struggles they face as a result of the world around them, whether it’s due to ableism and inaccessibility, society and culture, friends and family and peers, doctors and healthcare systems, state violence and the prison system, racism and systemic oppression, etc. I think this is very telling and a great reminder for all: While being sick and disabled is difficult and comes with many challenges, sometimes our greatest difficulties do not come from our disability itself, but from the people and world around us. It makes me wonder: How would life improve for disabled people if we didn't have the additional challenge of constantly contending with ableism and inaccessibility? Though we can’t change our bodies or our disabilities (and many of us wouldn’t want to), we can and should work to change the world around us. Awareness is key in attaining that change, and Disability Visibility does a great job raising awareness for many of these issues.

#3: Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice

by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha

“The sick and disabled spaces I have been in, been changed by, helped make, stumbled within at their best have been spaces full of deep love. And that deep love has been some of the most intense healing I’ve felt. It is a love that the medical-industrial complex and ableist society don’t understand.... We all deserve love. Love as an action verb. Love in full inclusion, in centrality, in not being forgotten. Being loved for our disabilities, our weirdness, not despite them. Love in action is when we strategize to create cross-disability access spaces. When we refuse to abandon each other. When we, as disabled people, fight for the access needs of sibling crips... When disabled people get free, everyone gets free. More access makes everything more accessible for everybody... So when you work to make spaces accessible, and then more accessible, know that you can come from a deep, profound place of love... know that the daily practice of loving self is intertwined with any safe room, accessible chairs, ramp. Both/and. When they are there, they show our bodies that we belong." -Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha (Pg 77)

Summary: Care Work is a love letter to disabled people, inviting us to be in community, practice disability justice, and dream a world where disabled people can support each other, advocate for each other, and create networks of care.

Topics discussed: What disability justice is, experiments in creating collective access (a network of disabled people offering and receiving support from other disabled folks), crip emotional intelligence and crip skills, advocating for each other's access needs, making spaces accessible as an act of love and solidarity, how to actually "do" disability justice and how beautiful and messy it is, crip mentorship and crip doulas, crip elders and ancestors, crip lineages and futures, plus chapters that demonstrate the importance of a disability justice framework by discussing issues that affect multiply marginalized people in activist spaces, such as femme leadership and hyperaccountability, self care and "working class and poor-led models of sustainable hustling for liberation", and emotional labor that is disproportionately forced upon poor and working class, Indigenous, Black, and brown femmes.

Content Warning: this book discusses potentially triggering topics such as abuse and suicide, especially in the second half of the book (Part 3). Read with care.

My main takeaway: How beautiful it is to be in community with fellow disabled people, and how to advocate, support, and care for each other.

Discussion: Care Work was a warm fuzzy blanket for my lonely crip soul. As a disabled person, I often feel as if I am living in a completely different world than everybody else, and one of my first thoughts while reading this book was how comforting it was to hear from someone who actually lives on the same planet. Reading Piepzna-Samarasinha talk about planning workshops for a conference with other disabled folks while simultaneously being “completely fucking stressed out” about how they were going to survive that conference was my first hint that this is a person who understands my life. I related deeply to their description about having a “freak-out about how badly the whole thing will fuck up your body” (Pg 48), and recognized all too well the overwhelming string of anxious concerns: “Will there be bathrooms? Will there be food I can eat? What if I have sensory overload or a panic attack 2000 miles from home?” This book was like hearing someone speak my own language for the very first time. On the surface, of course, I knew there were plenty of chronically ill and disabled people out there, but reading the in-depth details of the same exact thought processes that I have to consider every time I leave the house was a paradigm shift for me. It helped me reach that visceral knowing that I am truly not alone.

I didn’t know I could have such intimate community with others. Piepzna-Samarasinha goes on to describe traveling to the conference with a group of thirteen disabled people crammed into a wheelchair-accessible van meant for four, and everyone helping each other along the way. The group shared information on fragrance-free products beforehand so they could all be together safely, and booked accessible dorm suites so they could sleep and hang out together throughout the trip. One neurodivergent person who didn’t have mobility issues walked a mile to pick up take-out for everyone, using another person’s spare manual wheelchair to transport the food back to the hotel (Pg 50). At the conference, the group helped each other with access challenges, checked on each other when someone was all spooned out, and rolled together in “a big, slow-moving group of wheelchair users, cane users, and slow-moving people” to make sure no one was left behind (Pg 50). Reading about these experiences of community was inspirational to me. Never did I think I could be surrounded by people who actually understand, where I don’t have to hide those parts of me and we can all be our whole selves together. I didn’t know I could have that expectation or dream that dream of having true connection and community with others. I suspect that many disabled people don’t.

After the conference, a few group members decided to try a similar care network at home in the Bay area, providing and receiving care from each other within this community of disabled queer and trans people of color. This collective care web experiment lasted about a year, and though the group ultimately broke up, there was useful knowledge gained from the experience that Piepzna-Samarasinha shares with readers, including advice, tools, and pitfalls, as well as questions to ask yourself and keep asking as you attempt to build your own care web. Despite the challenges they faced during the experiment, it is clear that it did not dull Piepzna-Samarasinha’s enthusiasm and belief in the idea of care webs: "Crips supporting crips! Only! Ever! Crip-on-crip support is awesome! Often, after a lifetime of ableist able-bodied people providing shitty or abusive care and assuming that we’re not able to do anything ourselves, disabled people caring for each other can be a place of deep healing" (Pg 64). Crips supporting crips is such a beautiful thought, and reading about care networks inspired me to want to try this in my area someday too. Who better to take care of us than us? Wouldn’t it be lovely to build our own community of in-person support and not feel so alone?

Care Work is also empowering. We are often viewed by society as being deficient, broken and in need of a cure, that we can only be cared for and have nothing to offer in return. On the contrary, Piepzna-Samarasinha points out that we have a culture, special knowledge, emotional intelligence, and crip skills that run counter to all that. We have an understanding of the world and skills that able-bodied people don't have access to (yet). Piepzna-Samarasinha names some of these gifts that we have to offer, and I recognized quite a few as the special knowledge that I have gained because of my illnesses and disabilities, too. For example:

Knowing not to assume anything, and always asking.

The ability to read someone’s face, body language, and energy to tell they are in pain, fatigued, overwhelmed, triggered, or struggling.

Understanding isolation: "Deeply. We know what it’s like to be really, really alone. To be forgotten about. How being isolated, being shunned… can literally kill you.” But also that being alone can be “an oasis of calm, quiet, low stimulation, and rest” (Pg 71).

I recognized Piepzna-Samarasinha’s own special crip knowledge throughout the book, and the little details make this book so relatable. For example, the discussion about when an abled person becomes sick and suddenly everyone springs into action, but not when it’s us; how it’s hard not to be bitter from the isolation and abandonment by our communities; being offered intrusive, unsolicited medical advice every day of our lives, and that we’re expected to “be grateful for anything anyone offers at any time” (Pg 145). While these are difficult moments that I have experienced— and I imagine most, if not all, chronically ill and disabled people have— knowing that you are not alone in experiencing them really lightens that emotional pain and can be a powerful tool for coping and healing.

My favorite part of this book was the discussion on crip doulas, a concept created by Stacey Milbern which describes “other people who help bring you into disability community or into a different kind of disability than you may have experienced before. The more seasoned disabled person who comes and sits with your new crip self and lets you know the hacks you might need, holds space for your feelings, and shares the community’s stories” (Pg 132). Piepzna-Samarasinha and Milbern “wondered together: How would it change people’s experiences of disability and their fear of becoming disabled if this were a word, and a way of being? What if this was a rite of passage, a form of emotional labor folks knew of—this space of helping people transition? I have done this with hundreds of people. What if this is something we could all do for each other?” (Pg 132). This concept of crip doulas really resonated with me and I wondered too: How would this change the disability experience? Would it help the transition into disability feel less scary? Would we be able to recognize this as a rebirth rather than a death sentence?

The discussion on crip doulas made me think about my own content and audience. For some folks, my content is their first time seeing a disabled person accepting and embracing her disabilities and finding a way to do the things she loves with those disabilities. I strive to be a good representation *of* the disabled community and *for* the disabled community, which to me, means three things:

Avoiding ableism, inspiration porn, and the myth of the Super Crip.

Being honest about what it’s actually like to be disabled, and acknowledging that disability can be difficult and challenging.

Showing that it’s okay to be disabled, normal to be disabled, and that we can still live full lives.

My hope is to demonstrate and model what crip life can be like if we step away from the ableist worldview we’ve been raised with. It doesn’t have to be the doom-and-gloom, fate-worse-than-death, bitter-cripple or inspiration-porn, sad-and-tragic version of disability we’ve all been conditioned to believe is the only one that exists. Yes, sometimes disability is awful and shitty and it’s okay to acknowledge those difficult aspects, but disability is not solely a tragedy and it is certainly not a death sentence. I want to show people that being or becoming disabled is not the end of the world; we adapt and find new ways of living that work for our bodies, we adjust and this new life becomes our normal, and we may even find that there are lessons to be learned and beauty to be found unique only to this experience. It’s possible to lean in, embrace our disabilities, step more fully into our disabled lives, and find community, pride, joy, and solidarity with others.

Care Work is a beautiful invitation to do just that. May we all learn from the wisdom of elder crips and crip doulas, like Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha.

#4: A Disability History of the United States

by Kim E. Nielsen

“The story of US history is often told as a story of independence, rugged individualism, autonomy, and self-made men (and occasionally women) who, through hard work and determination, move from rags to riches.... Dependency means inequality, weakness, and reliance on others. When disability is equated with dependency, disability is stigmatized. Citizens with disabilities are labeled inferior citizens. When disability is understood as dependency, disability is posited in direct contrast to American ideals of independence and autonomy. In real life, however, just as in a real democracy, all of us are dependent on others. All of us contribute to and benefit from the care of others—as taxpayers, as recipients of public education, as the children of parents, as those who use public roads or transportation, as beneficiaries of publicly funded medical research, as those who do not participate in wage work during varying life stages, and on and on. We are an interdependent people.... "In real life no one is self-made; few are truly alone.” Dependency is not bad—indeed, it is at the heart of both the human and the American experience. It is what makes a community and a democracy." -Kim E. Nielsen

Summary: A Disability History describes the changing definitions, perceptions, and attitudes around disability throughout American history, as well as the legislation, activism, and movements, as told through the lives of people with disabilities in the historical record.

This book explains: How definitions, conceptualizations, and perceptions of disability have changed throughout American history, as well as how these definitions have intersected with race, gender, sexuality, and class in very specific and consequential ways. Darker moments in our history are discussed, such as institutionalization, ugly laws, forced sterilization, and eugenics, as well as the enslavement and dehumanization of Africans and the genocide of Indigenous peoples through conquest and disease. A Disability History also describes important legislation, from the Revolutionary War Pension Act of 1818 to the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, as well as examples of disability community, solidarity, resilience, joy, and activism, as told through the brief glimpses into the lives of individuals with disabilities in the historical record.

My main takeaway: How definitions of disability have changed over time and depended on intersectional identities.

Discussion: The biggest lesson I learned from A Disability History is that definitions of disability have changed over time and depended largely on social and cultural factors. As Nielsen points out, “Disability is not as clearly defined as we think, it is often elusive and changing,” and, “Disability is not just a bodily category, but instead and also a social category shaped by changing social factors- just as is able-bodiedness.” Who was considered disabled, how we perceived them, and how we treated them has varied so much, and is closely intertwined with other identities like race, gender, sexuality, and class.

For example, in the 1600s, physical disabilities would not have been outside the norm because of how difficult life was, between accidents, disease, and birth, so people with physical disabilities were given little attention as long as they could perform labor. Instead, substantial attention was given to people with cognitive and mental disabilities by the European colonists who were looking to establish social order and government (Pg 19). These cognitive and mental disabilities, however, were not considered to be particularly shameful until the 1800s, when perceptions and attitudes began to change. As a result, people with cognitive disabilities who were once cared for by family members were increasingly being forced into institutions by the 1870s (Pg 72). Additionally, throughout history, disabled people who came from wealthy families were treated differently than the way poor disabled people were treated, disabled women were treated differently than disabled men, and Black or Indigenous disabled people were treated differently than white disabled people. We can observe this happening in the historical record, and we can continue to witness it happening today.

The thing I loved most about this book was how much I related to the disabled people of the past, despite the centuries and cultures separating us. It's funny how I can have such a hard time relating to most contemporaneous able-bodied folks within my own time and culture, and yet feel an immediate connection and kinship with disabled people who lived hundreds of years before me. Apparently, disability is a powerful unifier across time, space, and culture.

At times, the stories told were funny and lighthearted. I loved reading about Jack Downs, who, in the 1700s, "regularly enjoyed plucking wigs off the heads of church worshippers with a string and a fishhook, and was well known for throwing rotten apples at the minister during the sermon" (Pg 36). Or the children with polio in the early 1900s who stayed up late at night in their hospital wards to have pillow fights, spitball battles, and wheelchair races (Pg 138).

At other times, this book is very emotional and difficult to read. It is never easy being confronted with the stories and details of what we did to Indigenous peoples, African Americans, and disabled people of all races, genders, sexualities, and classes. For example, the widespread disease epidemics that decimated Indigenous populations, the first of which in 1616-1619 killed 90-95% of the Algonquin people in New England (Pg 15). Or the outbreak of opthamalia (a highly contagious eye condition) on a slave trade ship called Le Rodeur, which resulted in many of the enslaved people on board becoming blind. Blindness reduced profits, so the captain tied 39 enslaved Africans to a ballast and threw them into the sea (Pg 44).

Stories like these are all too common in our history, and one in particular that not enough people are taught is that enslaved Black women were operated on without consent or anesthesia during experimental surgeries. One of the “vicious tenets of scientific racism” was that Black people don't feel pain due to their “racially defective bodies”— a myth that continues to have harmful consequences for Black women receiving medical care today (Pg 62). It was because of this racist belief that a woman named Anarcha endured 30 of these torturous surgeries, performed by a medical doctor who is considered one of the founders of modern gynecology. My stomach turns thinking about the fact that this doctor's name is in the history books and is likely praised for the knowledge he gained by torturing enslaved Black women, but Anarcha's name is not.

However difficult it is to read, it is important to know where we came from, because it's unfortunately all too easy to find ways in which history is repeating itself in the twenty-first century. The story of the 1840 census stuck with me in particular. This census showed that free Black folks experienced significantly higher rates of intellectual, cognitive, and psychological disabilities than those who were enslaved, which was a direct result of enslavers abandoning disabled slaves to starve and fend for themselves while continuing to enslave the most able-bodied and able-minded. However, slavery apologists used these census statistics as propaganda and "proof" that Black people are inherently "deficient" and in need of enslavement in order to keep them from going insane from freedom (Pg 64). I couldn’t help but think about how this story is analogous to today: we've created the conditions for Black people to be disproportionately harmed by state violence, but instead of pointing to the history of oppression, inherent systems of inequality, and implicit bias in our society, some people still claim that this higher percentage of Black people in prison is somehow "proof" of propensity to violence or criminality. It's pure racism and equally absurd to the claims of the slavery apologists in the 1800s. In both cases, we can trace exactly why these statistics occur, yet the willfully ignorant refuse to acknowledge these facts in favor of unfounded racist beliefs. (To read more about this, I highly recommend the book The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander.)

The last example I wanted to share is from 1977, during one of the many demonstrations in protest of the government’s failure to enforce anti-discrimination laws that had passed a few years prior (Pg 167). I loved reading about the allyship demonstrated in the 504 sit-in protest in San Francisco. As the group of disabled people performed their 25 day long sit-in protest, they received support from a gay rights group, Chicano activists, and the Black Panthers, who brought food for them every day and, at one point, walkie talkies. It's a beautiful reminder and demonstration of how we should support each other in our fight against injustice and inequality, because we are always stronger together and our fights are inextricably linked. As Maya Angelou said, “No one of us can be free until everybody is free.”

#5: Skin, Tooth, and Bone: The Basis of Movement is Our People

A Disability Justice Primer by Sins Invalid

“Disability justice holds a vision born out of collective struggle, drawing upon legacies of cultural and spiritual resistance. Within a thousand underground paths we ignite small persistent fires of rebellion in everyday life. Disabled people of the global majority — Black and brown people — share common ground confronting and subverting colonial powers in our struggle for life and justice. There has always been resistance to all forms of oppression, as we know in our bones that there have also always been disabled people visioning a world where we flourish, a world that values and celebrates us in all our beauty.” -Sins Invalid (Pg 20)

Summary: Skin, Tooth, and Bone is the handbook for Disability Justice; a vision, practice, and movement-building framework for a second wave of disability rights that strives to address the full extent of ableism, centering marginalized people in order to ensure that no body is left behind.

The book includes: The ten Disability Justice principles (intersectionality, leadership of the most impacted, anti-capitalist politics, cross movement solidarity, recognizing wholeness, sustainability, commitment to cross-disability solidarity, interdependence, collective access, and collective liberation). Access suggestions for public events (such as ASL, quiet spaces, food options, and no fragrances/chemicals). Access suggestions for mobilizations like protests and marches (including giving a verbal description of the march route beforehand, creating large print versions of written materials, providing and announcing a seated area and a low stimulation area). Solidarity statements addressing police violence (an estimated 50% of people killed by police are disabled), Palestine, and reproductive justice. The importance of mixed ability organizing, and the principles of this commitment (including valuing people as they are, valuing their contributions and insights, exploring and creating new ways of doing things that go beyond able-bodied and able-minded normativity). And finally, a couple of pieces by the Deaf community about audism and Deafhood, and a call to action from those with environmental illnesses and injuries.

My main takeaway: What the ten disability justice principles are, how to practice them, and why this framework is so important, plus lots of ideas for making events more accessible.

Discussion: The Disability Rights movement was undoubtedly an important step toward equality for disabled people, but it was also a product of its time and focused on a single-issue identity, leaving out important intersections of race, gender, and class. When Disability Rights focused solely on the experiences of white men with mobility impairments, it left out people with other types of disabilities and "invisiblized" people with disabilities who are also people of color, trans and queer, houseless, incarcerated, immigrants, and/or had their ancestral lands stolen (Pg 15). It focused on the most privileged while excluding both the experiences and the contributions of multiply marginalized people. Additionally, while Disability Rights addressed the systems of inequality, it did not address the root: ableism.

So, in 2005, “disabled queers and activists of color began discussing a second wave of disability rights," the authors explain. It was through these conversations, primarily between Patty Berne and Mia Mingus, but also including Leroy Moore, Stacey Milbern, Eli Clare, and Sebastian Margaret, that "launched the framework called disability justice" (Pg 17). A year later, Patty Berne and Leroy Moore would have another conversation that led to the creation of Sins Invalid, an art-activist performance project and the group that authored this book.

This second wave of disability rights attempts to fill in the gaps of the Disability Rights movement by attempting to address the core of the issue (ableism) while centering the most marginalized in order to ensure that nobody is left behind. Sins Invalid explains the importance of this change in framework: "One cannot look at the history of US slavery, the stealing of Indigenous lands, and US imperialism without seeing the way that white supremacy uses ableism to create a lesser/other group of people that is deemed less worthy/abled/smart/capable. A single issue civil rights framework is not enough to explain the full extent of ableism and how it operates in society. We can only truly understand ableism by tracing it's connections to heteropatriarchy, white supremacy, colonialism, and capitalism" (Pg 18). The Disability Justice framework therefore takes a more holistic approach, taking into account all systems of oppression, acknowledging the importance of intersectional identities, and radically proclaiming that all bodies are beautiful. As a quote in the handbook states, "All bodies and minds are unique and essential. All bodies are whole. All bodies have strengths and needs that must be met. We are powerful not despite the complexities of our bodies, but because of them. We move together, with no body left behind. This is disability justice” (Pg 12).

Skin, Tooth, and Bone was at the top of my reading list, because I wanted to gain a deeper understanding of Disability Justice, the ten disability justice principles, and how to implement them into my advocacy work. As a disability advocate, and especially as a disability advocate who has white cis/het privilege, it is my goal and my responsibility to ensure that I am advocating for all disabled people, whether I am directly affected by a particular issue or not. It is important to me that I don’t leave anybody behind or perpetuate harm in my community, so I strive to continue learning and unlearning, acknowledging and reflecting on my privilege, and listening to those who have lived experiences different from my own. Skin, Tooth, and Bone was not only informative of the Disability Justice framework and principles, but it was also a great demonstration and model of how to actually achieve these goals in my advocacy work.

While I primarily read this book to learn how to be a better advocate, I related to many parts of this book, too. I couldn’t help but smile at the introduction when Sins Invalid shares, “We wrote these words while living out our cripped out realities...while on heating pads, while on painkillers, while twisting in pain” (Pg 6), which is exactly where I am writing this right now. I also appreciated the chapter on environmental illness, because I too am a canary in a coal mine (my IG handle used to be @thegeneticcanary). I was surprised to see this topic included, because I’m used to this group of illnesses being so obscure even within chronic illness communities. People with environmental illnesses face a lot of stigma in the medical world and in daily life because our illnesses are so unknown, so it was really validating to see my illness being acknowledged.

Two other discussions I appreciated on a personal level were the mixed ability organizing and reproductive justice chapters. The principles of mixed ability organizing include valuing people as they are, and valuing both the process and the products of our work. As a disabled person and a woman, I often feel like my contributions are overlooked since they don't involve making money and I tend to move at a snail’s pace while able-bodied people run laps around me. The thought of my hard work and contributions actually being acknowledged and appreciated is something I did not know I needed, and it’s good to be reminded that what I do matters, too. I wish this wasn't such a radical thought, but that's precisely why we need disability justice and its anti-capitalist politics.

The other discussion I appreciated was on reproductive rights, and I hope this chapter will bring clarity on the disability community’s complex relationship to abortion laws. Some folks mistakenly believe that disabled people will be happy about restricted abortion access, because it would prevent people from practicing eugenics by preventing them from being able to (safely, legally) terminate a pregnancy due to a fetus having a disability. What these people seem to forget is that disabled people need access to abortions too, and the disabled community’s long history of forced sterilization, institutionalization, and being “forced to terminate pregnancies under the pretense that we cannot be good parents because we are disabled,” make many of us strong advocates for bodily autonomy (Pg 62).

The section I enjoyed the most was the access suggestion chapters. I couldn’t help but feel excited at the idea that maybe someday in the future, we will have events where these access accommodations are standard. What a difference that would make in who is able to attend events, myself included. There were some access suggestions that I hadn’t even thought of before that would make events more accessible for me. For example, including access information on promotional materials, providing food options and a low stimulation quiet space at an indoor event, or describing the route at an outdoor march and providing seating at the destination. It made me think about the events I’ve wanted to go to in the past but did not or could not attend, and how I might have been able to go if I had had these accommodations and the information about these accommodations in advance. This book is a must have for every person who is involved in event coordinating- whether they’re planning marches and protests or concerts and conferences.

There were also some access needs that I did not know about that I will be incorporating in my life and activism going forward. For example, in the discussion on the use of fonts, they mention that sans serif fonts are easier to read because they don’t have the tails at the edges. I hadn’t heard this before and will be using only sans serif fonts from now on. There was also a discussion about fragrance-free products at events to make it safe for people with MCS, and this is something I’ve been thinking about myself lately, too. I recently noticed that I occasionally use products that have a very powerful scent, and I’m concerned I might cause harm to whoever is within a 20 foot radius of me and catches a whiff of my soap, deodorant, or mousse. So, I am going to start exploring fragrance-free products and switching over as many as I can. Disability solidarity is one of the disability justice principles, after all!

Solidarity is an important principle, not just across disabilities but across movements as well. Sins Invalid’s solidarity statements on police violence, Palestine, and reproductive justice gave me a better understanding of how the disability justice principles apply in real life situations at the intersections of race, sexuality, and gender, and were a great demonstration of how to practice what you preach. I have a lot of respect for Sins Invalid’s approach to disability rights, justice, and to the community as a whole. After their first edition of this book, Sins Invalid asked for feedback from the community to determine what should be changed or added to the second edition, and the second edition has an open invitation to give feedback as well. This is clearly a community-led movement rather than a one-man show, which is particularly important in disability activism because, as we discussed earlier, we all have different experiences and no one disabled person can know everything about disability. Additionally, Sins Invalid is realistic about the practice of disability justice. They acknowledge that we all make mistakes and that they get it wrong too sometimes, but that they strive to learn and do better in the future. They also mention during the access suggestions chapters that it’s okay to start small with accommodating one or two access needs, and planning to grow from there. These two points make disability justice and improving accessibility more approachable, because there’s less pressure to demand ourselves to be perfect right at the start. All of us would benefit from integrating not only the main disability justice principles into our activism, but these small details that Sins Invalid models as well, like asking for feedback, always striving to do better, and having an inviting and understanding approach.

I hold Sins Invalid’s vision and practice of disability justice in high regard, and I wish every disability activist would become familiar with their work. Skin, Tooth, and Bone will undoubtedly be known as one of the most important disability rights books of our time.

Bonus! Crip Kinship: The Disability Justice & Art Activism of Sins Invalid

by Shayda Kafai

“Crip life invites us into fierce creativity. Because the world continues to treat us as worthless, creating new worlds is a matter of survival for us. Dreaming is a matter of survival. This is part of the power of Sins; we dream new crip worlds together." -Patty Berne (Pg 9)

If you're interested in reading more about Sins Invalid, their performance art, and how they created a movement, check out Crip Kinship by Shayda Kafai.

While the book centers around Sins Invalid's art and activism, Crip Kinship has beautiful wisdom for each of our lives too; sharing a vision and celebration of disability, community, and crip magic.

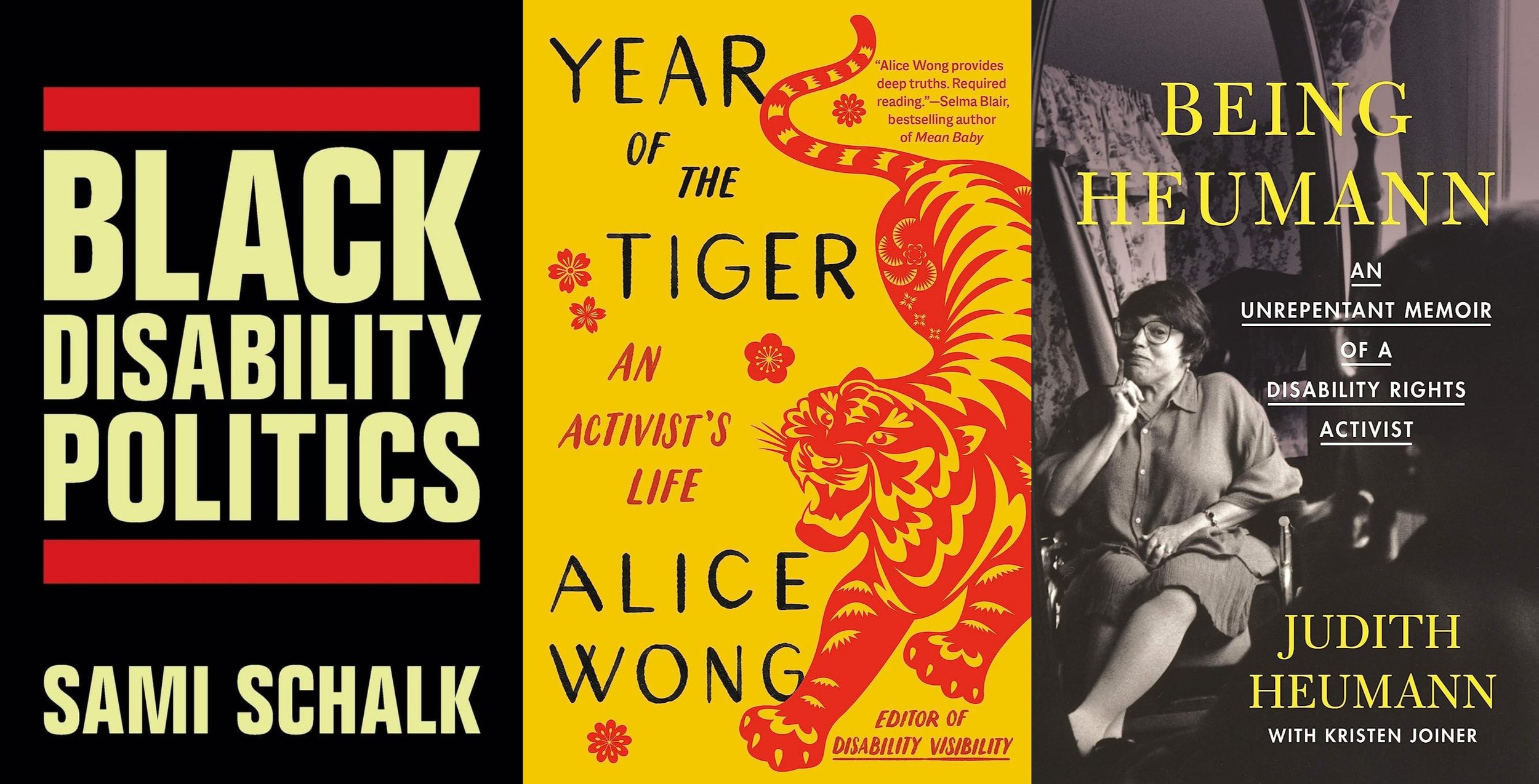

Next on My List

I loved reading these books and getting to know our community and our history. I consider myself to be a student of disability and I hope to continue learning both from my own personal experiences and from the experiences of others. Here’s what’s next on my reading list:

Black Disability Politics by Sami Schalk

Year of the Tiger: An Activist’s Life by Alice Wong

Being Heumann: An Unrepentant Memoir of a Disability Rights Activist by Judith Heumann

What’s on your reading list? Let us know in the comments!