What is Chronic Inflammatory Response Syndrome?

Written by Amy Denton-Luke

Chronic Inflammatory Response Syndrome is not yet a widely known illness, so when I tell people my diagnosis, their response is understandably, “What in the world is that?” It can be difficult to find reliable or easy-to-read information about my illness, so in this blog post I have put together a quick introduction into what CIRS is, how it is diagnosed, and how it is treated.

What Is CIRS?

Chronic Inflammatory Response Syndrome is a progressive, multi-system, multi-symptom illness characterized by exposure to biotoxins in genetically susceptible people.

Biotoxins can enter the body through inhalation, ingestion, tick and spider bites, and direct contact with contaminated water sources. The most common exposures are in water damaged buildings via the inhalation of a “biochemical stew” of fungi (including mold), bacteria, VOC’s, endotoxins, and actinomycetes. Tick-borne infections like borrelia and babesia, brown recluse spider bites, ingestion of reef fish contaminated with dinoflagellate algae that produces Ciguatera toxin, as well as direct contact with contaminated water of toxins like Pfisteria and cyanobacteria can also potentially cause CIRS.

When a non-susceptible person is exposed to these biotoxins, the biotoxins are recognized and bound by the immune system, then removed from the body through the stool. In genetically susceptible people however, the innate immune system detects the threat, but the adaptive immune system can’t “see” the biotoxins. The biotoxins are not recognized as foreign, no antibodies are produced, and the biotoxins therefore cannot be tagged, broken down, or removed. The biotoxins remain in the body indefinitely, passing from cell to cell causing cell damage while continuing to trigger a response from the innate immune system. This overactive immune response causes chronic, high levels of inflammation (hence the name Chronic Inflammatory Response Syndrome) which then leads to the dysregulation of multiple systems including many hormone-related dysregulations, as well as atrophy and inflammation in the brain.

In short, for genetically susceptible people, biotoxins cannot be removed by the immune system, so they remain in the body indefinitely, causing cell damage, immune system dysfunction, and system-wide inflammation, creating multiple symptoms across multiple systems, leading to chronic illness.

Left untreated, the symptoms can become debilitating, and include the following categories: general fatigue and weakness, muscles (aches/cramps, joint pain, morning stiffness, ice pick pain), neurological (numbness and tingling, metallic taste, vertigo, temperature regulation, dizziness, tremors, fine motor skill problems), cognitive (memory loss, concentration difficulties, confusion, learning difficulties, difficulty finding words, disorientation, mood swings, anxiety, panic, depression), gastrointestinal (abdominal pain, diarrhea, constipation), respiratory (sinus pain, cough, shortness of breath), eyes (light sensitivity, red eyes, blurred vision, tearing), and general (headache, frequent urination, increased thirst, night sweats, static shocks, appetite swings).

Because CIRS is not yet widely known or treated, it is often misdiagnosed as chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, multiple sclerosis, depression/anxiety, PTSD, IBS, autoimmune disorders, and possibly even neurodegenerative illnesses such as Alzheimer’s disease.

How is CIRS diagnosed?

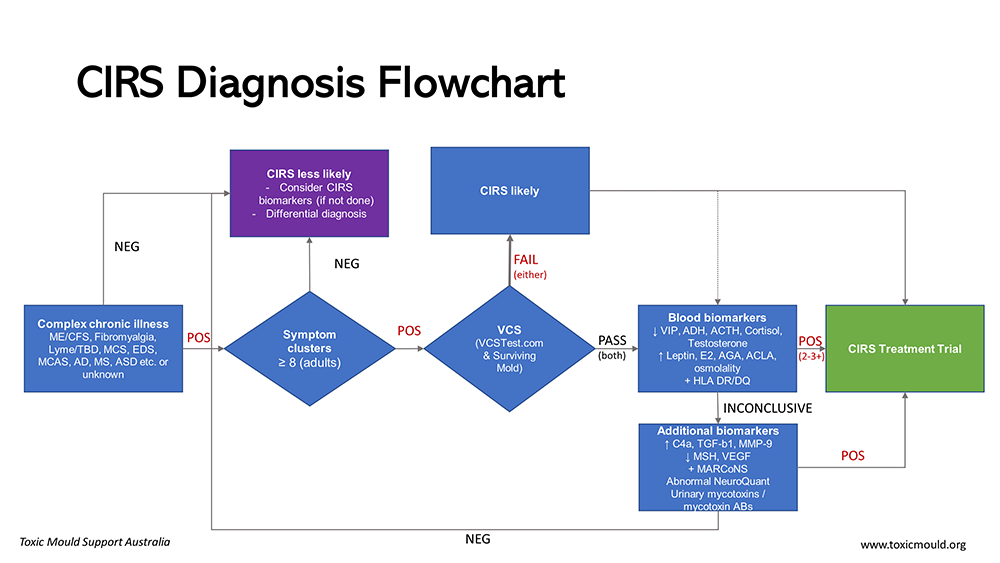

Biotoxins are extremely small, fat soluble molecules that can move from cell to cell through cell membranes rather than the bloodstream and are therefore difficult or even impossible to find in standard blood tests, which are often used for the diagnosis of other pathogens. Instead, a CIRS diagnosis begins with a list of symptoms and a history of exposure to a known trigger, followed by visual, genetic, MRI, and biomarker testing.

Nerve dysfunction from biotoxin illness will lead to neurological symptoms including diminished visual contrast sensitivity, so a visual contrast sensitivity (VCS) test is given at the initial appointment to confirm the likelihood of CIRS.

A patient is tested for genetic susceptibility by looking at their HLA genes (HLA-DR/DQ). An estimated 24% of the population has a “mold-susceptible” haplotype, and some people have HLA gene combinations that make them “multi-susceptible” to all biotoxins.

It’s also worth noting that 21% have a “Lyme-susceptible” haplotype, which may explain why some don’t recover from Lyme disease after antibiotic treatment. According to Dr. Shoemaker, antibiotics adequately kill the bacteria, but the circulating neurotoxins that cannot be removed by the genetically susceptible immune system continue triggering an inflammatory response, leading to long term illness.

Next is a long list of blood tests to check the biomarkers that are affected by CIRS, which will show the extent of the damage done by the biotoxins. These tests include: Melanocyte Stimulating Hormone (MSH), Transforming Growth Factor Beta 1 (TGF-B 1), Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF), Matrix Metallopeptidase 9 (MMP-9), C4a, Anti-diuretic hormone (ADH), Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide (VIP), and more.

Specific biotoxins may also be tested for including MARCONS (via nasal swab), Epstein Barr, and Lyme. If mold is suspected, environmental tests through an accredited lab like Envirobiomics or Mycometrics can be performed on a patient’s home and/or workplace to confirm the source and severity of their exposure. Another useful diagnostic tool is the MRI Neuroquant Analysis, which can show damage (atrophy or swelling) to specific structures of the brain caused by biotoxins.

All of these tests will provide a full picture of the patient’s unique case, which will determine their treatment steps.

How is CIRS treated?

The most documented, evidence-based treatment for CIRS is called the Shoemaker protocol, developed by Dr. Ritchie Shoemaker over the last 25+ years, and involves removing the patient from exposure, removing the biotoxins from their body, then correcting the biomarker abnormalities to repair the damage and restore function.

The first step to treating CIRS is removal from ongoing exposure to biotoxins. About 80% of CIRS patients are ill from the biotoxins produced by mold in water damaged buildings, so this first step for many means no longer living, working, or going to school in moldy buildings. This can be a challenge considering that, statistically, 50% of buildings have sustained water damage.

If the source of mold exposure is in the home, remediation by a professional mold remediation company is required, as well as a complete surface cleaning of the home and all belongings. Remember: mold is a living organism that reproduces via spores that can spread throughout the house, contaminate belongings, and will continue to grow. So, after fixing moisture issues, water damage, and removing the mold source, cleaning all surfaces and possessions is an extremely important step in preventing re-contamination, cross-contamination, and continued exposure.

Additionally, if the patient has an active infection of Lyme or co-infections, a round of antibiotics are given. MARCONS, bacteria that colonize the nasal cavity, require a nasal spray medication to break down biofilms and kill the bacteria.

Once a patient is no longer actively being exposed to biotoxins, they must remove the biotoxins from the body. Because a genetically susceptible person’s immune system is not capable of doing this on its own, a medication called ‘binders’ are required. The medicine “binds” to the biotoxins in the GI tract and carries them out via the stool. This process can take months, or even years, and often causes symptoms to intensify as the biotoxins begin to mobilize and temporarily increase inflammation.

Once enough biotoxins have cleared, there are a series of steps to correct the biomarker abnormalities, which is achieved through various medications, supplements, and a no-amylose diet. The final step in the Shoemaker Protocol is a nasal spray called VIP, a synthetic version of the neuropeptide that helps regulate hormone function and normalizes inflammatory processes.

With the appropriate treatment steps, it is possible to heal from Chronic Inflammatory Response Syndrome.

. . .

Of course, treatment is not always as straightforward as doctors would like for it to be. Some people have simple cases who respond very well to the treatment steps and may only require a few months to recover. Others of us, however, have more complicated cases with hypersensitive systems that suffer through years of treatment while enduring a body and brain on fire.

Furthermore, sometimes remediation is not possible, and some CIRS patients will lose their homes. Some will lose all of their belongings. Some will struggle to find safe housing and end up living in their cars or tents in the desert to keep themselves safe. Some of us are so hypersensitive during treatment that any re-exposure is detrimental to our progress, and to avoid pouring gasoline on a raging fire, we must practice “extreme mold avoidance” and isolation, limiting ourselves only to spaces that have been tested and confirmed safe, which are quite often our homes and nowhere else.

It’s one thing to read through the definitions and treatment of CIRS, but the reality of the lived experience is quite another…

Part Two coming soon.

If you think you may have CIRS, visit survivingmold.com and go to “Find Physicians”

Resources

Overview of CIRS

Chronic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (CIRS) Evaluation and Treatment by Dr. Bruce Hoffman

Chronic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (CIRS) Explained by Sean Di Lizio

More In-Depth Information

Overview of Research Committee Report on CIRS

Other Interesting Reads

As I see it: Lyme Disease and CIRS

Study: Type 3 Alzheimer’s may be late-stage CIRS

An Interview with Dr. Shoemaker

Public Hearing on CIRS in Australia

Books

Mold Warriors by James L. Schaller, Patti Schmidt, and Ritchie C. Shoemaker

Surviving Mold by Ritchie C. Shoemaker

Mold Illness: Surviving and Thriving: A Recovery Manual for Patients & Families Impacted By CIRS by Paula Vetter et al